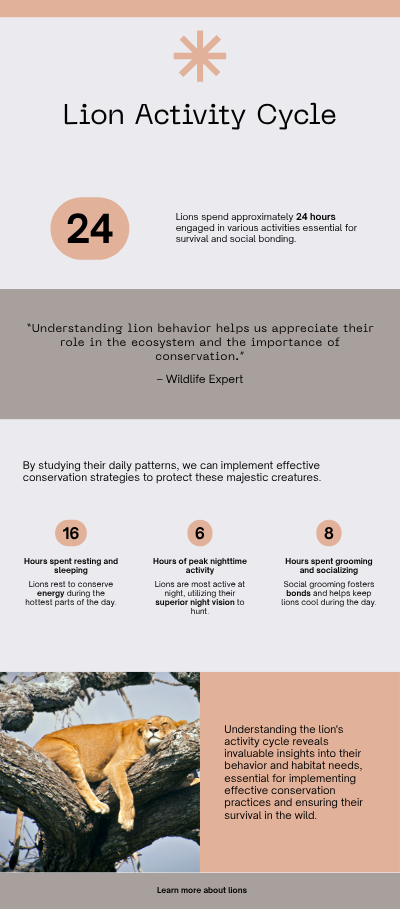

Do Lions Hunt at Night? Discover Their Nocturnal Secrets

Africa's apex predator, the lion, commands respect not just for its raw power, but for its sophisticated hunting strategies that have evolved over millennia. While these magnificent cats rest lazily under acacia trees during scorching afternoons, a different story unfolds when darkness blankets the savanna.

Are lions truly kings of the night?

Lion hunting at night in African savanna at dusk

Lion hunting at night in African savanna at duskWhy Lions Prefer Hunting at Night?

Lions have evolved as primarily nocturnal hunters, and this behavioral adaptation isn't coincidental—it's a masterclass in survival strategy honed over thousands of years.

Lion daily activity pattern showing peak hunting times at night and dawn

Lion daily activity pattern showing peak hunting times at night and dawnTemperature regulation

Temperature regulation plays a crucial role in their preference for nighttime hunting. During African days, temperatures frequently soar above 95°F (35°C), making prolonged physical exertion dangerous even for these powerful predators.

Lions resting in daytime heat compared to active hunting at night

Lions resting in daytime heat compared to active hunting at nightHunting requires explosive bursts of energy, and overheating can quickly become fatal. By waiting for cooler evening and nighttime temperatures, lions conserve energy and reduce the risk of heat exhaustion during their pursuits.

Element of surprise

The element of surprise dramatically increases after sunset. Lions possess tawny coats that blend seamlessly with golden grasslands during the day, but darkness transforms them into virtually invisible phantoms.

Their prey—zebras, wildebeests, buffalo, and antelopes—rely heavily on visual detection to avoid predators. When visibility drops, so does their ability to spot danger until it's too late.

Reduced prey alertness

Reduced prey alertness gives lions another significant advantage. Many herbivores feed intensively during daylight hours when they can see predators approaching from a distance.

At night, these same animals become more vulnerable while resting or moving cautiously through unfamiliar territory. Their nervous systems aren't as primed for immediate flight response, and their reaction times slow considerably in low-light conditions.

Additionally, nighttime hunting allows lions to exploit the natural behavior patterns of their prey. Many herbivores move to water sources during evening hours, creating predictable congregation points where lions can stage ambushes.

This strategic positioning eliminates the need for exhausting, open-ground chases.

Day vs Night Hunting Patterns

The hunting success rate of lions varies dramatically between daylight and darkness, revealing fascinating insights into their predatory efficiency.

Research conducted in African wildlife reserves shows that lions achieve a success rate of approximately 25-30% during nighttime hunts, compared to just 15-20% during daytime pursuits. This substantial difference isn't merely about visibility—it reflects a complex interplay of environmental factors, prey behavior, and pride coordination.

Nighttime hunting behaviors showcase the lion's tactical sophistication:

- Prides move in coordinated formations, with experienced females positioning themselves strategically around potential prey

- Communication becomes almost entirely non-vocal, relying on subtle body language and positioning

- Hunting parties typically consist of 2-6 lionesses working in synchronized patterns

- The approach phase takes longer at night, sometimes lasting over an hour as lions maneuver into optimal ambush positions

Daytime hunting patterns reveal different challenges and adaptations:

- Hunts tend to be shorter and more opportunistic, taking advantage of isolated or weakened prey

- Success depends heavily on exploiting terrain features like tall grass, rocky outcrops, or dense vegetation for concealment

- Lions often target younger or sick animals that can't maintain the vigilance required to detect daytime predators

- Solo hunts become more common during daylight hours, particularly by experienced females

|

Night Hunting: |

|

The group dynamics shift noticeably between day and night. Nighttime hunts involve more pride members working collaboratively, with clearly defined roles.

Some lionesses act as "drivers," pushing prey toward ambush points where others wait. During the day, smaller groups or individual lions attempt faster, more direct approaches that require less coordination but offer lower success rates.

Interestingly, lions in certain regions have adapted their hunting schedules based on prey availability. In areas where herbivores are predominantly nocturnal or crepuscular (active during twilight), lions adjust accordingly, demonstrating their remarkable behavioral flexibility.

The Role of Eyesight in Night Hunting

Lions possess extraordinary visual adaptations that transform them into formidable nocturnal predators, giving them a decisive advantage over their prey when darkness falls.

The secret lies in their eye structure. Lions have a specialized layer of cells behind the retina called the tapetum lucidum—a reflective membrane that acts like a biological mirror. When light enters the eye, this layer reflects it back through the retina, essentially giving photoreceptor cells a second chance to capture photons. This adaptation allows lions to see in light conditions that are six times dimmer than what humans require for vision.

Key visual advantages lions possess at night include:

- Enhanced light sensitivity: Their pupils can dilate to approximately twice the size of human pupils, allowing more light to enter the eye

- Superior motion detection: Lions excel at detecting movement in peripheral vision, even in near-total darkness

- Binocular vision: Forward-facing eyes provide excellent depth perception, crucial for judging distances during the final sprint toward prey

- Rod-rich retinas: A higher concentration of rod cells (specialized for low-light vision) compared to cone cells means exceptional night vision, though with reduced color perception

When you see the characteristic green or golden eye-shine of a lion at night, you're witnessing the tapetum lucidum in action—light reflecting back out of the eye, which is why lions' eyes seem to glow when caught in headlights or moonlight.

How prey species counteract lion vision:

Despite lions' superior night vision, their prey haven't remained defenseless. Herbivores have developed counter-adaptations, creating an ongoing evolutionary arms race. Many prey species have eyes positioned on the sides of their heads, providing nearly 360-degree vision to detect approaching predators. They've also evolved highly sensitive hearing and acute smell to compensate for reduced visibility.

Zebras, for instance, rely on their excellent night vision (also possessing a tapetum lucidum) combined with herd vigilance—the "many eyes" principle where at least some individuals remain alert while others feed or rest. Wildebeests use loud, distinctive alarm calls that can alert an entire herd instantly when danger is detected.

However, these defenses become less effective during the darkest nights. On moonless evenings or during new moon phases, even well-adapted prey struggle to detect lions' stealthy approaches, which is why hunting success rates peak during these periods.